As 2026 approaches, the word revival is spoken with increasing frequency in the language of the Western Church, repeated across conferences, broadcasts, and prophetic discussions with a sense of anticipation that often lacks the weight of Scripture, history, and lived obedience, because revival, as it is described biblically, has never arrived as a cultural event or a spiritual atmosphere detached from repentance, surrender, and cost. The persistent difficulty in the current moment is not that revival is being spoken of too little, but that it is being spoken of too easily, as though it were a seasonal expectation rather than a divine response to collapse.

For many years now, particularly in the American Church, revival has been prophesied annually with remarkable consistency and remarkably little consequence. Each year brings new declarations, familiar vocabulary, and renewed expectations, yet the underlying posture of the Church remains largely unchanged. Revival is announced, but rarely examined. It is anticipated, but seldom interrogated. The language continues, while the life required to sustain it is postponed. Over time, prophecy risks becoming cyclical rather than consequential, enthusiasm replacing repentance, and anticipation substituting for obedience. When revival is reduced to language that costs nothing, it loses its authority.

Throughout history, revival has never emerged from safety, convenience, or institutional comfort, and yet much of the Western Church continues to approach it as something that can coexist with cultural acceptance, personal prosperity, and unchallenged routines. Scripture does not support such an expectation. Revival has always been God’s response to collapse—moral collapse, institutional collapse, and spiritual collapse—not to stability or success. When systems that once promised meaning, order, and protection fail, hearts turn back to God not because they are inspired, but because they are exposed. Revival, in its truest sense, is not spectacle; it is return.

This return inevitably exposes the Church itself. The years ahead will not simply test governments, economies, or social systems; they will reveal which expressions of Christianity were built on culture, performance, influence, and visibility, and which were built on Christ alone. Much of what passed for faith in the West was sustained by social approval, political proximity, and institutional protection. As those supports weaken, celebrity Christianity, political Christianity, and performance-based faith will lose their ability to endure. What remains will not be louder or more visible, but more rooted, because it will no longer be sustained by comfort. This is not condemnation; it is discernment, and discernment has always been an act of mercy.

Pressure has a clarifying effect that comfort never produces. As hostility toward biblical Christianity increases—sometimes through legislation, sometimes through professional exclusion, sometimes through social rejection—the difference between belonging and believing becomes unavoidable. History offers no example of persecution destroying the true Church. On the contrary, persecution has consistently purified it. From the first centuries of Christianity, when believers were driven underground and worshiped in secret, to the Reformation, when obedience to Scripture cost reformers their freedom and their lives, to modern underground churches in hostile regimes, persecution has functioned as a refining fire rather than a terminating force.

The Book of Acts does not describe revival emerging from protection or endorsement, but from resistance. The early Church expanded because it was pressed, not because it was affirmed. Pressure stripped away superficial attachment and convenience faith, leaving behind those who had already counted the cost of following Christ and were therefore no longer governed by fear. Where faith carried a price, faith carried power.

This pattern did not end with the apostolic age. It repeated itself wherever the Gospel confronted power without compromise. In the Roman world, persecution forced the Church into homes and catacombs, where faith deepened without visibility. During the Reformation, obedience to Scripture dismantled ecclesiastical safety and cost believers their property, their freedom, and often their lives. In the twentieth century, underground churches across Eastern Europe, China, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America learned to live without platforms, recognition, or protection, yet emerged spiritually resilient, doctrinally anchored, and uncompromising in witness.

History shows that when the Church aligns too closely with institutional power, it grows numerically but weak in authority; when it is stripped of protection, it grows smaller but unmistakably strong. Revival has never been the preservation of a system. It has been the reappearance of truth after systems fail.

Persecution Is Not a Concept — It Is Loss, and It Produces Fruit

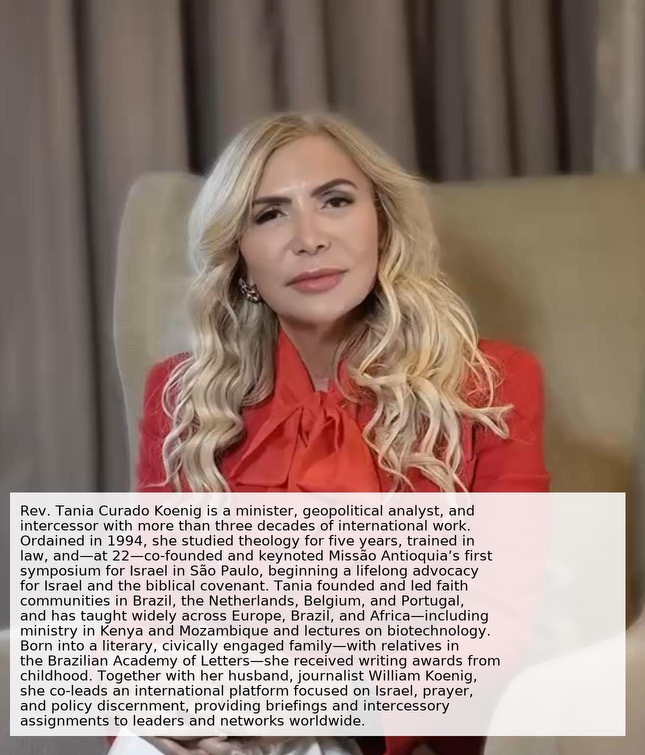

I do not speak of persecution as a metaphor, nor as a theoretical category reserved for history books or distant nations. I speak of it as lived reality. When I came to Jesus Christ, the cost was not gradual or symbolic; it was immediate and concrete. I lost my home. I lost my place of security. I was abandoned by family and friends, treated not as someone who had chosen faith, but as someone who had lost reason. There were attempts to have me institutionalized, to frame my conversion as psychological instability, simply because I had become evangelical and spoke openly about Jesus Christ. Conviction was medicalized. Faith was pathologized.

In the countries where I lived and served, persecution took physical form. In the Netherlands, hostility was systematic and humiliating. In Portugal, while opening churches, I was beaten, spat upon, publicly harassed, and threatened. This was not occasional resistance or misunderstanding. It was sustained opposition directed at the name of Christ. There was no protection, no institutional backing, no cultural buffer. Faith meant exposure, vulnerability, and loss.

Yet what is often misunderstood in the West is that persecution does not weaken the Gospel — it clarifies it. Above all, every time the persecution became heavier, more people gave their lives to Jesus Christ. Families were restored. Sick people were healed. In Portugal, every day we would enter homes and break idols as people chose Christ openly and decisively. Opposition did not diminish the work; it purified it. This was not spectacle. It was daily obedience lived under risk.

This is why persecution cannot be separated from revival. It strips faith of performance and leaves only truth. It removes ambition and replaces it with surrender. It exposes motives and reveals what is real. Revival does not follow persecution as a reward; it emerges within it as evidence that God is present and active where obedience costs something.

This is why I cannot speak lightly about revival. Persecution is not disagreement. It is not criticism. It is loss of safety, dignity, and belonging. And yet it is precisely there — not after persecution, but within it — that I encountered the sustaining power of God. Revival did not come after comfort returned. It came when there was nothing left to rely on but obedience.

This distinction matters profoundly as the American Church approaches 2026. A Church that has never been stripped does not understand how to stand when stripping comes. A Church that has never lost position does not know how to obey when obedience costs status. This is why so much prophetic language sounds hollow to those who have lived under real persecution. It is not that the words are false; it is that they are weightless.

Scripture does not call the Church to improvement, but to transformation. “Present your bodies as a living sacrifice,” the Apostle Paul writes, “holy and acceptable to God, which is your reasonable service” (Romans 12:1). This is not symbolic language. A sacrifice costs something real. The primitive Church understood this instinctively. They did not ask whether obedience was safe; they asked whether it was faithful. They did not ask whether following Christ would preserve their lives; they asked whether it would honor Him.

The next move of God may therefore bypass many of the institutional structures the Western Church has relied upon. Historically, revival has often flowed through small gatherings, homes, prayer groups, and informal networks rather than through large denominational machinery. Simplicity replaces programs. The Word replaces entertainment. Prayer replaces strategy. Communion replaces branding. Obedience replaces optimization. This pattern is already visible globally, and it resonates most strongly where faith has never been a cultural default.

At the same time, 2026 marks a converging moment between Israel and the Church. As antisemitism rises openly across societies that once claimed moral progress, so does prayer for Israel among believing Gentiles, alongside a renewed awakening to Israel’s place in God’s redemptive purposes. Scripture anticipated this convergence long ago. Paul speaks of it in Romans 11, and the prophet Zechariah describes it as a moment when hearts are pierced and intercession deepens. This is not a political alignment; it is a spiritual recalibration, calling the Church back to humility, watchfulness, and prayer.

Revival, stripped of illusions, removes every add-on the Western Church has accumulated. It carries no prosperity guarantees, no political messianism, and no fear-based speculation. It returns the Gospel to its center: Christ crucified, Christ risen, Christ obeyed. Cross before crown. Obedience before power. Love before influence. Anything else proves unsustainable under sustained pressure.

This moment forces a decision the Western Church has postponed for decades: whether it will continue to interpret grace as insulation from cost, or rediscover grace as the power to endure it. Comfort has shaped expectations more than Scripture, and convenience has quietly replaced consecration. Yet revival does not coexist with comfort. It interrupts it. Where faith remains negotiable, revival remains theoretical. Where obedience becomes costly again, revival becomes unavoidable.

The global Church already understands this. In many parts of the world, Christianity has never been safe, fashionable, or institutionally protected. Believers there do not ask whether faith will cost them something; they assume it will. That assumption has preserved depth, humility, and dependence on God. The Western Church is now being invited into that same posture — not as punishment, but as restoration.

For this reason, revival in 2026 will not be loud. God does not compete with chaos, nor does He advertise repentance. True revival unfolds quietly, through conviction rather than spectacle, through repentance rather than repetition, through lives laid down rather than platforms expanded. It advances not through virality, but through faithfulness.

If the Church continues to prophesy revival without learning what persecution is, the words will remain empty. If it chooses instead the path of living sacrifice—renouncing the flesh, returning to repentance, fasting, obedience, and the way of the primitive Church—revival will not need to be announced.

It will be unmistakable.